In the forward to his book, A Craftsman Remembers, Gordon Hansford writes that for every front line soldier engaged in combat during WWII, ten served behind the lines in various capacities, the so called “administrative tail of the army.”

Called Craftsmen by the army, these were the soldiers who served as mechanics, electricians and engineers, and when situations called for it, as diggers of latrines and graves. These were the men and women who rarely reached the front line but were never far from it; the soldiers, to paraphrase Winston Churchill’s famous dictum, who also served the war effort by serving behind the lines.

Hansford’s book, which was recently published, is the story of one of those soldiers who served as a Craftsman during the war. “I choose not to write about the horrors of war,” he said in effect, “but about behind the line soldiers and the many jobs we did that kept the war machine running.”

Hansford does this admirably, creating a wonderful record of what it was like for the ordinary soldier serving behind the lines. While he writes in the first person about his war years, his story portrays the unknown Canadians soldiers who served, survived and continued on afterwards uncelebrated and for the most part, rarely recognized for their contributions.

Gordon Hansford served overseas during the war for more than three years, taking part in campaigns in Africa, Sicily and Holland. For those who know Hansford, he’s a genial man with a finely tuned sense of humour and more stories than Google has hits. He displays this sense of humour and a bit of irony as well, throughout the book. His being mistaken for a doctor while hospitalized and treating a malingerer is hilarious and is one example of the sort of humour found in his book.

Hansford’s story starts in Wolfville where he became interested in the military at an early age, recalling that at age seven he marched around the streets of Wolfville wearing his father’s World War 1 gear. In 1941, in his mid-teens, Hansford enlisted in the local unit of the West Nova Scotia Regiment at Aldershot Camp as a bandsman. That year he decided to join what he called “the real army” and by the spring of 1942 he found himself at the Canadian Army Trade Schools in Halifax. After additional training with the Royal Canadian Ordnance Corp in Ontario, Hansford was shipped to England, arriving there early in 1943.

This is where Hansford’s war story really starts. He takes his readers through the major campaigns the Canadian Army participated in, always with a story or two, leaving us with an intimate look at how the war affected everyone involved. Most of my generation had someone close to us who participated in the war. Those participants, our fathers, brothers, uncles, cousins and next door neighbours, often refused to talk about their war experiences. Hansford’s book starkly reveals what he and all those other Canadians caught up in the war went through; he breaks the silence and this makes the work an invaluable record. The book aptly could have been subtitled, The Canadian Soldier, His War behind the Lines, since this is what it’s all about.

Privately published by Hansford and his wife, Helen, copies of the book are available at the Kings County Museum where they’re being sold as a fundraiser.

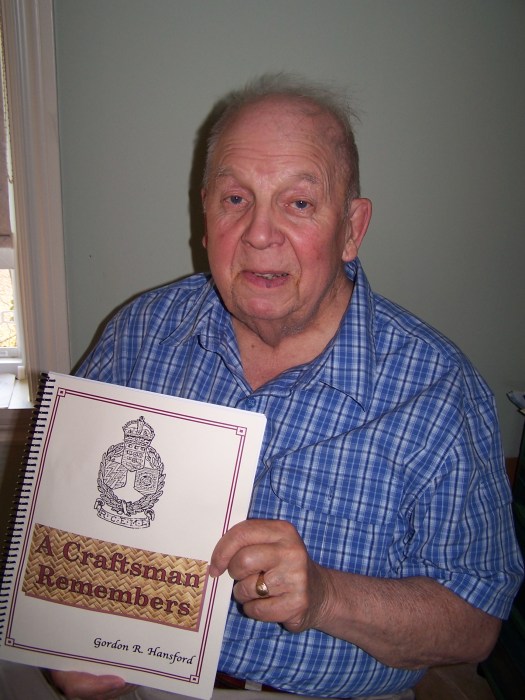

Gordon Hansford, above, with his book on soldiering behind the lines in WWII. (E. Coleman)